This post is the first of a three-part series about Zane Grey, the father of the modern Western novel, who spent time in Eastern Washington in the early 1900s to write his agrarian-themed novel The Desert of Wheat.

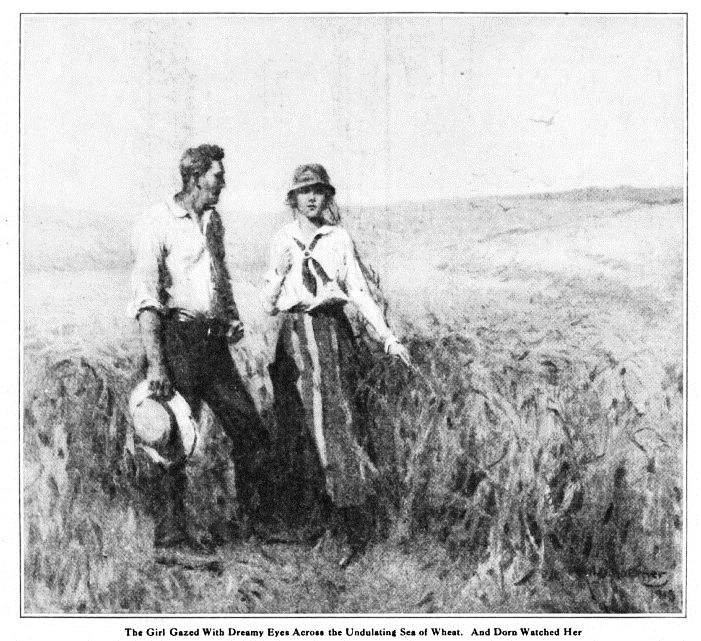

Grey’s novel relates the tragic end of protagonist Kurt Dorn’s father, Chris, who collapses while fighting a crop fire. While recovering from the loss and challenge of bringing in his grain from the field, Kurt is unexpectedly greeted by “a wonderful harvest scene.” Neighbors from all around his home gather for a grand threshing bee to complete the harvest. Grey cleverly uses this special “American” event—commonly seen in rural areas for families in distress, to describe the complicated and labor-intensive process of grain harvesting operations in an era of horse- and steam-power. Kurt arose to see “the glaring gold of the wheat field… crisscrossed everywhere with bobbing black streaks of horses—bays, blacks, whites, and reds; by big, moving painted machines, lifting arms and puffing straw; by immense wagons piled high with sheaves of wheat, lumbering down to the smoking engines and the threshers….” Few other novelists provide such colorful and detailed narration of the harvesting sequence from cutting by combine and reaper to threshing and hauling the year’s precious yield to storage:

First Kurt began to load bags of wheat, as they fell from the whirring combines…. For his powerful arms a full bag, containing two bushels, was like a toy for a child. With a lift and a heave he threw a bag into a wagon. They were everywhere, these brown bags, dotting the stubble field, appearing as if by magic in the wake of the machines. They rolled off the platforms.

…From that he progressed to a seat on one of the immense combines, where he drove twenty-four horses. No driver there was any surer than Kurt of his aim with the little stones he threw to spur a lagging horse. …[H]e liked the shifty cloud of fragrant chaff, now and then blinding and choking him; and he liked the steady, rhythmic tramps of hooves and the roaring whir of the great complicated machine. It fascinated him to see the wide swath of nodding wheat tremble and sway and fall, and go sliding up into the inside of that grinding maw, and come out, straw and dust and chaff, and a slender stream of gold filling the bags.

A Northwest Harvest Scene Postcard, c. 1910, Palouse Heritage Collection

With the successful completion of harvest providing payment on the farm’s mortgage (Kurt sought no favors from Lenore’s sympathetic landlord father) and resolution of further WWI turmoil, young Dorn finally feels free to enlist in the army. Following basic training in the East, he is transported to the front lines in France where he experiences the brutalities of war. Grey paints the ugliness of battle in vivid terms that also express the wastefulness of violent conflict. While an ardent patriot who decried foreign aggression, Grey also uses dialogue and description to relate the horrific long-term consequences of war for survivors frequently overlooked in contemporary press accounts. The injuries Dorn incurs going over the top of a trench amidst machine-gun fire, panic, gas-shelling, and bombardment nearly end his life. The scene is less heroic than nauseous in “pale gloom, with spectral forms,” and death. He returns home as a broken man haunted by hideous dreams and devoid of hope for the future. Once again the abiding power of love and land shown through Lenore in their native fields of Columbia grain bring forth meaning and restoration:

Then clearly floated to him a slow sweeping rustle of the wheat. Breast-high it stood down there, outside his window, a moving body, higher than the gloom. That rustle was the voice of childhood, youth, and manhood, whispering to him, thrilling as never before. …The night wind bore it, but life—bursting life was behind it, and behind that seemed to come a driving and mighty spirit. Beyond the growth of the wheat, beyond its life and perennial gift, was something measureless and obscure, infinite and universal.

Suddenly he saw that something as the breath and the blood and the spirit of wheat—and of man. Dust and to dust returned they might be, but this physical form was only the fleeting inscrutable moment on earth, spring up, giving birth to seed, dying out for that ever-increasing purpose which ran through the ages.

With the completion of The Desert of Wheat in 1918 and lucrative contracts from Harper’s for future works, Grey and his wife, Dolly, relocated from Pennsylvania to southern California in 1920 and acquired a Spanish-Mediterranean Revival mansion near Pasadena. He had long been an avid outdoorsman, and his financial success led to worldwide fishing expeditions and support of conservation efforts. Although one of America’s most prominent authors, Grey had still harbored doubts about his continued capacity for creative writing. But the recent Western travels and popular acclaim for The Desert of Wheat fostered renewed commitment and a turning point in his career. His journal entry of February 16, 1918 records, “…[M]y study and passion shall be directed to that which I have already written best—the beauty and color and mystery of great spaces, of the open, of Nature and her wild moods.”

The commercial success of Grey’s books led in 1920 to his formation of a motion picture company, Zane Grey Productions. The company released a silent movie version of The Desert of Wheat which played in theatres nationwide as Riders of the Dawn. He eventually sold the company to Paramount Studios but continued writing short stories novels for the rest of his life and consulted for later Hollywood productions of dozens of films based on his books.

Paxton Farrar, “Zane Grey House” from Starry Night (2016)

The Desert of Wheat also inspired Paxton Farrar’s award-winning 2016 short film Starry Night funded by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. Farrar cited “the vastness of the landscapes” and “melancholic romance that permeates the land” as important cinematic influences. In Farrar’s presentation the main character is a young woman who seeks escape from small town life to pursue her passion to become an astronomer. The film’s starlit scenes evoke young Dorn’s evening soliloquy as he surveys the cosmos and expresses an eloquent philosophy of life uncharacteristic of a Western novel: “Material things—life, success—such as had inspired Kurt Dorn, on this calm night lost their significance and were seen clearly. They could not last. But the wheat there, the hills, the stars—they would go on with their task. …[S]elf-sacrifice, with its mercy, succor, its seed like the wheat, was as infinite as the stars.” Whether returning to familiar Southwest scenes and frontier action for new novels, or while sailing to the South Pacific, Grey’s time on the Columbia Plateau left a favorable and enduring impression.